Balzoi Harvey gently runs his palm over the smooth bronze figures adorning the stout African throne, tenderly admiring the intricate engravings and spiritual symbolism of the 250-pound sculpture.

In Cameroon , the solid bronze seat would be reserved for a king of the Bamun tribe, a regal perch from which to receive visitors and make official decrees.

But in Harvey's incense soaked South Orange living room, the throne is tucked away in a corner by the fireplace, a favorite place for him to unwind to a jazz record and contemplate his African ancestry.

"This represents a pillow of peace for me to rest my head on," said Harvey, 65, a former diplomat and current head of the Essex County Economic Development Corp. "I've got a little piece of the past, things that happened way before I was born, done by my people."

With more than 300 African artifacts and art pieces representing over 100 distinct tribes, Harvey has more than just a little piece of the past. Throughout his home, iron weapons, wooden idols and Congolese drums spill off shelves onto the floor. In the center of one room sits an ancient tribal board game with dozens of carefully chiseled stone pieces, in another rests a green verdite bust from the Shona people of Zimbabwe, Masks from Mozambique to Mali cover an entire wall.

Africa scholars

and art dealers say Harvey's treasures, gathered over four decades and some 200 trips to the continent, stand as one of the premier private collections of traditional african art in the United States. Even many museum collections, they say, fail to match the diversity and uniqueness of the pieces found in Harvey's home.

Balozi does not have airport art; he has really authentic pieces." said Zain Abdullah, a professor of African American and African Studies at Rutgers University, Newark. "He has very unique pieces, and though they may not be as old as the pieces in some museums, he has pieces that aren't being made anymore."

Sousseyni Samake, a Malian art dealer based in Richmond, Va., said he has traveled throughout the United States for 25 years matching top collectors with rare African works, but has never come across another collection like Harvey's.

"All his pieces are originals from Africa, and they're mixed, from all different places," said Samake, noting that many of the pieces are worth several thousand dollars. " Of the private collectors I've seen, Balozi is the best."

The son of a lieutenant in Marcus Garvey's back-to-Africa movement and the grand-nephew of a freed slave sent to Liberia by the Presbyterian Church, it could be said that an affinity for Africa runs in Harvey's blood.

But the East Orange native – whose given name is Robert– said he was not drawn to the continent until taking a position with the Tanzanian Mission to the United Nations in 1961. Tanzania had just gained its independence from Great Britain, and Harvey- already active in the Black Power movement – immediately recognized the parallels between black Americans fighting for civil rights and black Africans fighting colonialism.

"They understood the struggle because they were struggling, too," he said.

But it was not until his first flight home from Africa that Harvey was introduced to the continent's art, when a fellow passenger showed him an art book he had bought as a souvenir .

"I was so amazed, it was like a magnet," he said.

He began studying art books himself, marking the pieces he liked with bright yellow stickers, then trekking to the remote villages where they were made. He found many of his pieces in his private collections of tribal leaders; others he rescued from artisans trapped in war-torn countries. Most of the more extravagant pieces – like the bronze throne – came as gifts from various African leaders he met during his two decades in foreign service.

As he collected, Harvey tried to bridge the gap between Africans and African Americans in the United States, using art to teach black Americans about African culture. He was a founding member of the Congress of African Peoples and arranged a series of formal balls in New York City where African dignitaries could interact with American black leaders. After leaving the diplomatic corps in 1982, he took a position with the Third World Trade Institute in Harlem, which fostered commerce between African markets and American Companies.

"He brought consciousness of Africa that was very important," said civil rights activist and poet Amiri Baraka. "He always tried to create a closer kind of unity and solidarity between Afro-Americans and Africans."

Harvey says he is not just a collector, but a custodian of the past, preserving history for future generations. He estimates 90 percent of his collection has been used in some sort of tribal ceremony.

"These are things that our ancestors, our forefathers have used. It's a collection I want to pass down to my children to let them see how we were," he said.

Married to East Orange Municipal Judge Karimu Hill-Harvey, he is father of six children, the youngest of whom is 20.

Harvey also has amassed a library of African newspaper clippings and photo albums chronicling each trip. In one album, he is shown traveling through Nigeria with Muhammad Ali. Another depicts former South African President Nelson Mandela's first visit to Harlem, A more recent album is filled with pictures of decaying corpses, photos taken by Harvey in 1994 when he toured the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide.

I don't want history to get lost like we lost our history in the past because we didn't write it down," he said "My father never went to Africa.... I've been back for him and all the other members of my family who never got a chance to go."

As his appreciation for African art has grown, so has Harvey's love for culture. In 1962, he changed his name to Balozi, which means "ambassador" in Swahili. Three years later, he converted from Catholicism to Islam, and in 1987 he began wearing traditional African dress once a week in homage to his friend President Sankara of Burkina Faso, who was assassinated that year.

He now no longer owns a Western-style suit, opting instead to pair dark slacks with a dashiki and matching kufi hat.

Harvey is an honorary king in three tribes and owns undeveloped property in Cote d' Ivory and Senegal. He speaks Wolof, Swahili, Zulu, Twi and Arabic.

"People say you are your environment," Harvey said of his relationship with Africa."Once I got in that environment, I knew who I was."

Contenient-wide collection

Balozi Harvey has more than 300 pieces of art in his collection, representing work from more than 100 distinct tribes. He acquired the art during the 200-plus trips he made to Africa while working as a diplomat.

The wooden two-headed dog sculpture is a symbol of a two-sided life, with both physical and spiritual worlds. The nails represent an attachment between the interconnected halves. Harvey acquired the 19th century sculpture in 2004 in Congo.

This Bronze sculpture from Brukina Faso depicts a Mossi King. it was molded using the "lost wax process." which created molds that must be destroyed to release the sculpture. The sculpture was made about 1960 and was a gift to Harvey from the country's president, Thomas Sankara, in 1987.

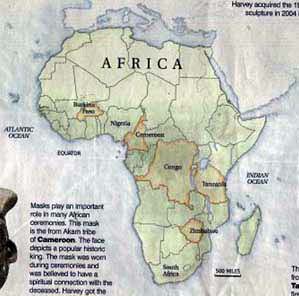

Masks play an important role in many African ceremonies. This mask is from Akam tribe of Cameroon. The face depicts a popular historic king. The mask was worn during ceremonies and was believed to have a spiritual connection with the deceased. Harvey got the mask about 20 years ago.

Balozi Harvey in his living room, amid some of the African art and artifacts he has collected over four decades

The 19th century wood carving from Kerbe, in north western Tanzania, was one of the first pieces of African art acquired by Harvey in 1963.

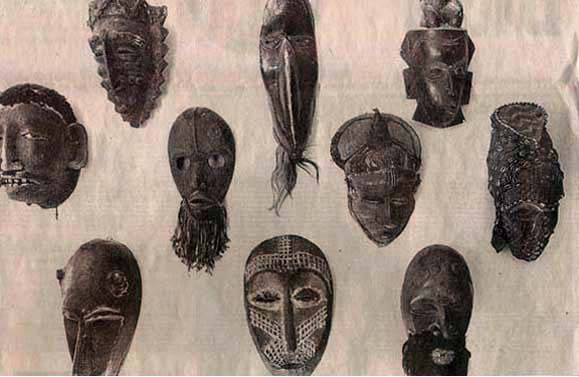

These ceremonial masks, among the more than 300 pieces of art in the collection of Balozi Harvey , hang on his wall in South Orange.

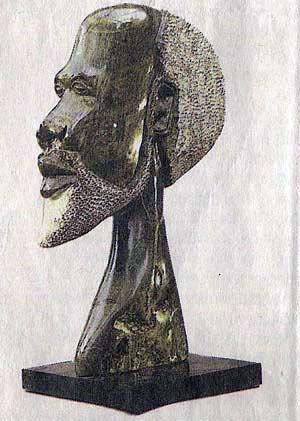

Harvey bought this statue from the Shona tribe of Zimbabwe in 1976 because it looked like his father. The statue is made from verdite, a semi precious stone found only in Zimbabwe.